A Poet, an Artist, and a Lady

Photo Credit: Joe Pulcinella

By Samantha Snyder

When a guest stepped through the front door of Samuel and Elizabeth Powel’s house, they entered into a different world. The sounds of the city, the clattering of carriages over the uneven cobblestones or the unpleasant smells of sewage permeating the humid air faded into the background. Instead, they were met with the hazy glow of candles, casting shadows along the central passage. If a guest had an invitation card in hand, they would pass under the privacy arch and be enveloped into the Powels’ world.

It is as though the Powels themselves can be seen at the top of the stairs, their perfectly balanced greetings of vivacity and generosity “shining forth with such fascinating influence,” that all who met them desired to be welcomed into their close circle of friends.[1] They would be ushered into the large drawing room (contemporarily referred to as the ballroom), which stretched the length of the house. The room was a source of great pleasure and pride for the Powels, as it was a rare feature of the townhouses in the city. They would hear the sounds of musicians tuning their instruments, ready to play sets of minuets and country-dances.

The Powels filled their walls with prints and portraits, highlighting their patronage of the arts. The Marquis de Chastellux, one of the many figures who visited the Powel’s home was so impressed with their collection; he noted it in his travel diary. Upon his first visit to their house in 1780, he observed it to be a “beautiful English house, adorned with beautiful prints and very good copies of the best paintings in Italy.”[2] Among those pieces, hung portraits of family and friends.

Engraving of Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, undated, courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

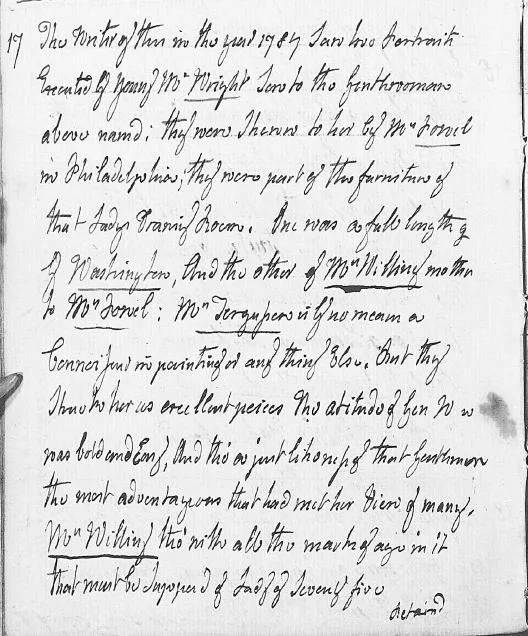

Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, one of the brightest literary stars of eighteenth century Philadelphia, and frequent visitor to the Powels’ house, has brought forth previously undiscovered information about two of these portraits, simply by making a note in her commonplace book. All within a few lines, she identified two of the portraits that hung on the walls, as well as the date of acquisition, and who the artist was.[3]

Note in Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson's 1789 Commonplace Book, courtesy of Graeme Park

The two subjects were George Washington and Anne Shippen Willing, Elizabeth’s mother. Fergusson wrote, “in the year 1784, [she] Saw two Portraits Executed by Young Mr. Wright...” which were “Shewn to her by Mrs. Powel in Philadelphia as a part of the furniture of that lady’s drawing room.”[4]

Portrait of George Washington, by Joseph Wright, 1784, courtesy of Drexel University

Portrait of Anne Shippen Willing, by Joseph Wright, ca. 1784, courtesy of PhilaLandmarks

Though Fergusson claimed she was “by no means a Connoisseur in painting or any thing Else,” the portraits “struck her as excellent pieces.” She goes on to describe them in great detail:

“The attitude of Gen W—n was bold and Easy, And tho’ a just likeness of that Gentleman the most advantageous that had met her View of many. Mrs Willing tho’ with all the marks of age in it that must be Supposed of Lady of Seventy five Retained that Chearfull expressive Countenance; And that urbanity thro the whole, which is so Correspondant to the Disposition of that Excellent Woman.” [5]

Joseph Wright, educated by Benjamin West (a former classmate of Samuel Powel’s and “historical painter to the court,” of King George III), spent his youth in England. He later traveled to Paris under the patronage of Benjamin Franklin, before making his way back to America in 1782. Wright made his debut in American society, eager to capture the likenesses of the fine men and women of Philadelphia.[6]

Drawing Room of the Powels’ Rhode Island Mansion, courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Washington portrait in the center)

Drawing Room of the Powels’ Rhode Island mansion, courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Willing portrait on the left)

The George Washington portrait has long been attributed to Joseph Wright. The Anne Shippen Willing portrait, however, has previously been attributed to Matthew Pratt. Both have made their appearances in both public and private places.

The portrait of George Washington now hangs outside of the tent exhibit at the Museum of the American Revolution. It has been displayed on many different walls, and been viewed by hundreds, if not thousands, of different eyes. It hung in the halls of the Atwater-Kent Museum and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Both portraits hung in the drawing room of the Powel family home in Rhode Island, a parlor in Elizabeth Powel’s Chestnut Street residence, and of course, in the drawing room at the Powel House. The prized portrait Elizabeth Powel’s mother, Anne Shippen Willing, now once again resides in the “withdrawing room,” (also known as the parlor) in the Powel House.[7]

Portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powel, by Joseph Wright, ca. 1793, courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association

The Powels not only commissioned Wright to paint portraits of their friends, but Elizabeth herself had her portrait painted by Wright. The Powels likely commissioned this specific portrait honor her fiftieth birthday, in February 1793.[8]

Tragically, Joseph Wright, his wife, and two of his four young children lost their lives to the Yellow Fever epidemic, which struck Philadelphia later that year, so the portrait remains unfinished. Elizabeth also suffered a great loss. Her beloved husband Samuel Powel succumbed to the fever two weeks before Joseph Wright and his family.

Check stub for payment for Mr. Wright’s children, courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

In December 1793, Elizabeth contributed $20 to a fund for the “use of Mr. Wright’s children,” collected by Samuel Hodgon, Superintendent of Military Stores.[9] Powel patronized other artists later in her life, though never to the extent of Joseph Wright.

1876 Note on letter from Elizabeth Powel to Hannah Bushrod Washington, courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association.

Years later, Elizabeth’s nephew John Hare Powel made it very clear that he did not hold the same affinity for the Washington portrait that his Aunt and her peers did. He, according to his son Samuel, “delighted to teaze [his Aunt] by saying Wright’s picture of Genl. Washington was badly painted.”[10] But, the art critic spoke too soon.

Mary Edith Powel, the oldest grandchild of John Hare Powel, followed in her father Samuel’s footsteps and became the Powel family’s historian in the late 19th-century. She left several handwritten memoirs about her youth, in which she describes her many visits to her grandfather’s house. She talks about the pieces of art that hung on the walls, including the Wright portrait of George Washington. She remembers it in what her grandfather called “The Picture Gallery,” which was the main hall of his Philadelphia mansion. Mary believed her grandfather “had the gift of recognizing the beautiful in art,” and he “esteemed the Wright portrait most highly...” quite a change from the playful teasing of his Aunt so many years prior. Guess that portrait wasn’t so bad after all! [11] Unfortunately, no further commentary on the Anne Willing portrait survives, but, considering its continual prominent display, it was likely “highly esteemed” as well.

So, thanks to a poet, an artist, and a lady, one more historical mystery is solved.

Of course, a special thanks to the following institutions for preserving the portraits and documents: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks, Graeme Park, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, and the descendants of the Powel family. I’m also indebted to those nineteenth century (and of course all the way up to the twenty-first century) Powels!

Bibliography:

1. “Bushrod Washington to Hannah Bushrod Washington, 11 June 1782,” Letters to his mother, 1782-1791, Accession #38-537, Special Collections Dept., University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

2. François Jean marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North-America, in the Years 1780, 1781, and 1782 (United Kingdom: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1787), 204.

3. For more information on the literary salonniere and good friend of the Powels’, see, The Most Learned Woman in America: A Life of Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, by Anne M. Ousterhout (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997). For an open-access article, see Martha C. Slotten’s article, “Elizabeth Graeme Ferguson: A Poet in ‘The Athens of North America.,’” in, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 108, no. 3 (1984): 259–88. ; For more information on Anne Shippen Willing, see Zara Anishanslin’s fantastic study of another portrait of Willing’s, in Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories in the British Atlantic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

4. This note comes after a long poem about Patience Wright, an intriguing woman who was not only a sculptor artist, and the mother of Joseph Wright... but also, a spy during the American Revolution. See: Charles Coleman Seller’s work, Patience Wright, American Artist and Spy in George III’s London (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1976), for more information on her life, involvement in the war, and interactions with George Washington.

The commonplace book, which is located in the collections at Graeme Park, dates to 1789, and is dedicated to the “Willing Sisters,” meaning the five daughters of Thomas Willing, the eldest brother of the Willing clan. Thanks to Carla Loughlin at Graeme Park for working out a way to get both the transcription and the scan of the commonplace book for me. Who knew it would hold this fantastic information!

5. “The Willing Commonplace Book (1787-1789),” Graeme Park Collections.

6. For more biographical information on Joseph Wright, see Monroe H. Fabian’s 1985 thoroughly researched exhibit guide, Joseph Wright: American Artist, 1756-1793 (Washington, D.C.,: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), 77-140.

7. The Wright portrait of George Washington has long been documented as a piece owned by the Powels. The first known mention (that this author can find) comes from an 1857 article, “Original Portraits of Washington,” in, Cosmopolitan Art Journal, 2, no. 1 (1857): 24–26. The most in-depth study of this portrait is from Nicholas B. Wainright’s “The Powel Portrait of Washington by Joseph Wright,” in, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 96 no. 4 (1972): 419–23.

The Joseph Wright portrait of Anne Shippen Willing first appears in an undated photograph of the Powel family’s drawing room in Rhode Island printed in Robert Johnston Powel’s Hare-Powel and Kindred Families (New York: privately printed, 1907), 104. According to William Sawitzky’s somewhat flawed study of the portraits of Matthew Pratt, the Willing portrait once was attributed to Charles Willson Peale before Sawitzky’s unsourced claim that the Willing portrait was instead painted by Matthew Pratt. However, the author may have been confused with a different portrait, dated 1773, which is a documented a Peale portrait of Anne Willing. Sawitzky’s study often reaches with its attributions, including misattributing the 1793 portrait of Elizabeth Powel (now in the collections of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association) to Pratt. David W. Maxey, in his study on a Matthew Pratt portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powel dated ca. 1786, A Portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powel, printed in, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 96, no. 4 (2006): i–91, also misattributes the Anne Shippen Willing portrait to Matthew Pratt, based on prior scholarship.

The Willing portrait’s pose and coloring matches several of Wright’s portraits, including the 1790 portrait of Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, located at the National Portrait Gallery.

8. The Powel portrait’s attribution to Joseph Wright is based on the research of Mount Vernon’s curators and portrait experts. For more information Joseph Wright’s catalogue of works, see Monroe H. Fabian’s 1985 thoroughly researched exhibit guide, Joseph Wright: American Artist, 1756-1793 (Washington, D.C.,: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), 77-140. Mount Vernon’s Curator of Fine and Decorative Arts found that Joseph Wright’s wife Sarah, in an unfinished 1793 family portrait titled “The Wright Family,” located at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, has a nearly identical dress and hairstyle to the unfished portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powel. Two additional portraits, of Hannah Bloomfield Glasse and Elizabeth Stevens Carle, formerly in the collections of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, have a similar pose, dress, and hairstyle.

9. Joseph and Sarah Wright, and two of Two of Joseph Wright’s four children survived the epidemic, left to the care of the state. Samuel Hodgdon seemed to be collecting funds on their behalf. This notation comes from “Materials Removed from Volume 41,” Series 3. Elizabeth Powel, Powel Family Papers, (LCP.in.HSP.91), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

10. John Hare Powel and Elizabeth Powel had a lasting, close bond. Upon her death, John inherited the majority of her personal and real estate, including a large swath of her and her husband’s artwork. John, like his Aunt and Uncle, was a patron of the fine arts, purchasing numerous paintings and sketches on his trips to Europe throughout his life. In 1843, he lent 39 paintings from his personal collection to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for their “Exhibition of Paintings, Statues, and Casts at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.” A handwritten list is located within PAFA’s archives (specifically, “List of Donations to PAFA 1809-1857, also pictures borrowed and returned,” Institutional Records, The Dorothy & Kenneth Woodcock Archives, PAFA.

Thanks to David Maxey for his writing an upcoming article on a different portrait. His inquiring if I’d come across Powel/PAFA related records led me to track down a microfilm collection of PAFA records that given the midst of COVID could not be visited in person. I came across this list, among numerous other pieces of documentation relevant to the Powels’ connection with PAFA, beginning in 1807.

For more on John Hare Powel’s fashionable taste in architecture, art, and furniture, see Charles B. Wood’s “Powelton: An Unrecorded Building by William Strickland” in, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 91, no. 2 (1967): 145–63, and, John Walsh Jr.’s article, “The Earliest Dated Paintings by Nicolas Maes,” in The Metropolitan Museum Journal 6, (1972): 105- 114.

11. “19th and Walnut Street memoir, volume 2,” Series 8. Mary Edith Powel, Powel Family Papers (1582), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.