HISTORIC WAYNESBOROUGH

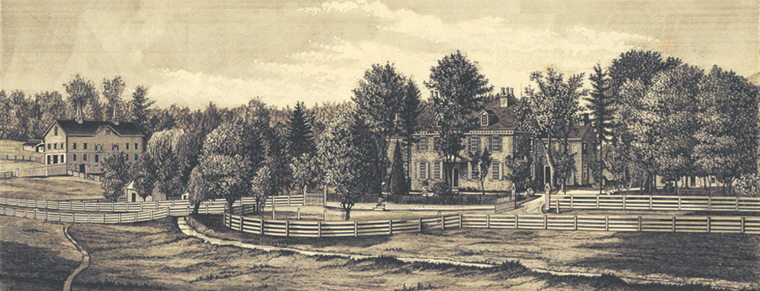

Waynesborough

Paoli 1724

Waynesborough is a National Historic Landmark in Paoli, PA. Situated on ten lush acres, the Georgian-style House was once the home of the colorful, brash and deeply committed Revolutionary War hero, General Anthony Wayne. Seven generations of the Wayne family continuously owned the property from 1724 until 1965. In 1980, a group of interested local residents and organizations together with Easttown Township raised funds to purchase Waynesborough from the current owner, to save this historic property and ensure it would be preserved for new generations of visitors.

Easttown Township, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission needed a skilled partner to administrate and preserve their newly acquired house museum and the sprawling 18th century estate linked to America’s Revolutionary War history. The group turned to the highly experienced PhilaLandmarks who agreed at once to take on the responsibility. Thus beginning a successful relationship now extending into its fourth decade.

Historic Waynesborough Grounds & Gardens

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

Historic Waynesborough Grounds & Gardens

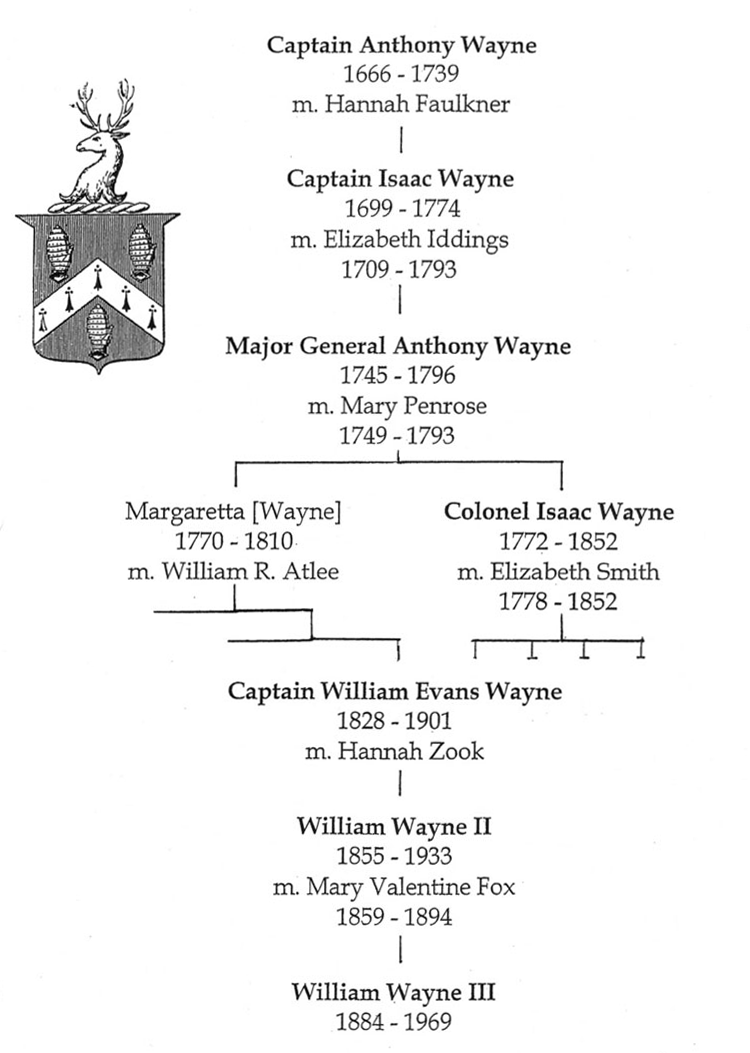

Seven Generations of Wayne’s

-

Seven generations of the Wayne family continuously owned the property from 1724 until 1965.

The original owner was Captain Anthony Wayne (1666- 1739), an Englishman who had fought valiantly for King William III of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne, which enabled William and the Protestants to assume the throne.

Seeking a change, the Captain and his wife, Hannah Faulkner, and most of their nine adult children emigrated to the Pennsylvania colony in 1724, purchasing 386 acres in Chester County, PA.

-

When the Captain died, the sprawling estate was passed on to his son, Isaac Wayne (1699-1774) who married Elizabeth Iddings and added a successful tannery business to the family’s farming operation.

Isaac then took a commission as an Officer in the French and Indian War. After he returned home, it was Isaac who began building the extensive Georgian manor house that would be the family home for the next 200 years.

-

Upon Isaac’s death in 1774, the family home passed on to his son, Anthony Wayne (1745-1796) who was to become the famous Major General Anthony Wayne, who served with General Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette during the American Revolution. Later Wayne helped secure the Northwest Territory for the United States.

Anthony Wayne married Mary (Polly) Penrose and they had two children Margaretta and Colonel Isaac Wayne (1772-1852).

-

During the War of 1812, Isaac Wayne equipped and commanded a Pennsylvania horse cavalry and was soon promoted to Colonel of the Second Pennsylvania Regiment. After the war, Colonel Wayne was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

When 4th generation Isaac died in 1852 without a living male heir, the property passed to his sister Margaretta’s grandson William Wayne (Evans) who was General Anthony Wayne’s Great Grandson and the 5th generation of Waynes.

In 1853, William married Hannah Zook. And resumed the family businesses. At the outbreak of the Civil War, William helped organize a home guard unit among the citizens of Paoli, the 97th Pennsylvania Infantry, and was named Captain.

In December of 1862, the 97th received orders to proceed to South Carolina where Wayne led his company through operations at Warsaw Sound, Georgia; Fort Clinch and Jacksonville, Florida; and Edisto, John, and the James Islands, South Carolina. After the war, Wayne served 3 terms in the U.S. Congress.

-

Captain Wayne and his wife Hannah’s son William Wayne II married Mary Valentine Fox and bore the 7th generation Wayne: William Wayne III who sold the estate in 1965, ending the dynasty at Waynesborough.

In 1980, the final owners sought a buyer who would ensure the estate’s preservation.

Easttown Township was selected to be its next owner, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and local supporters raised the funds to purchase Waynesborough.

In 1980, the group turned to the highly experienced PhilaLandmarks for help in managing and preserving the property for future generations to enjoy. Our organization agreed at once to take on the responsibility. Thus beginning a successful relationship now extending into its fourth decade.

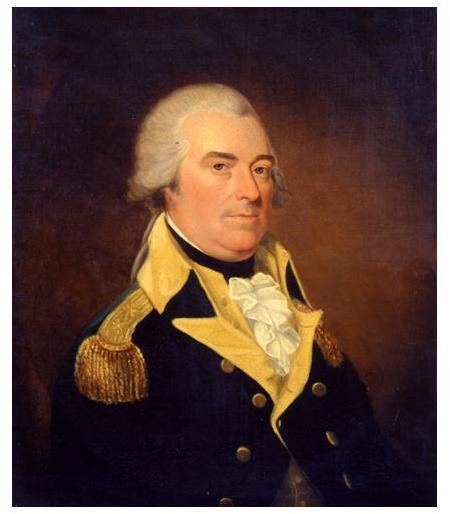

Meet General Anthony Wayne (1745 — 1796)

-

Waynesborough’s most famous resident Major General Anthony Wayne was born on January 1, 1745 on his family's 500 acre estate in Chester County, PA, one of four children born to Isaac and Elizabeth Iddings Wayne.

Anthony’s interest in the military began at a young age. His grandfather and father had both been soldiers. This inspired Anthony to want to learn more and he read avidly of historic battles and military heroes. He even regularly corralled his friends and cousins into armies to fight mock battles.

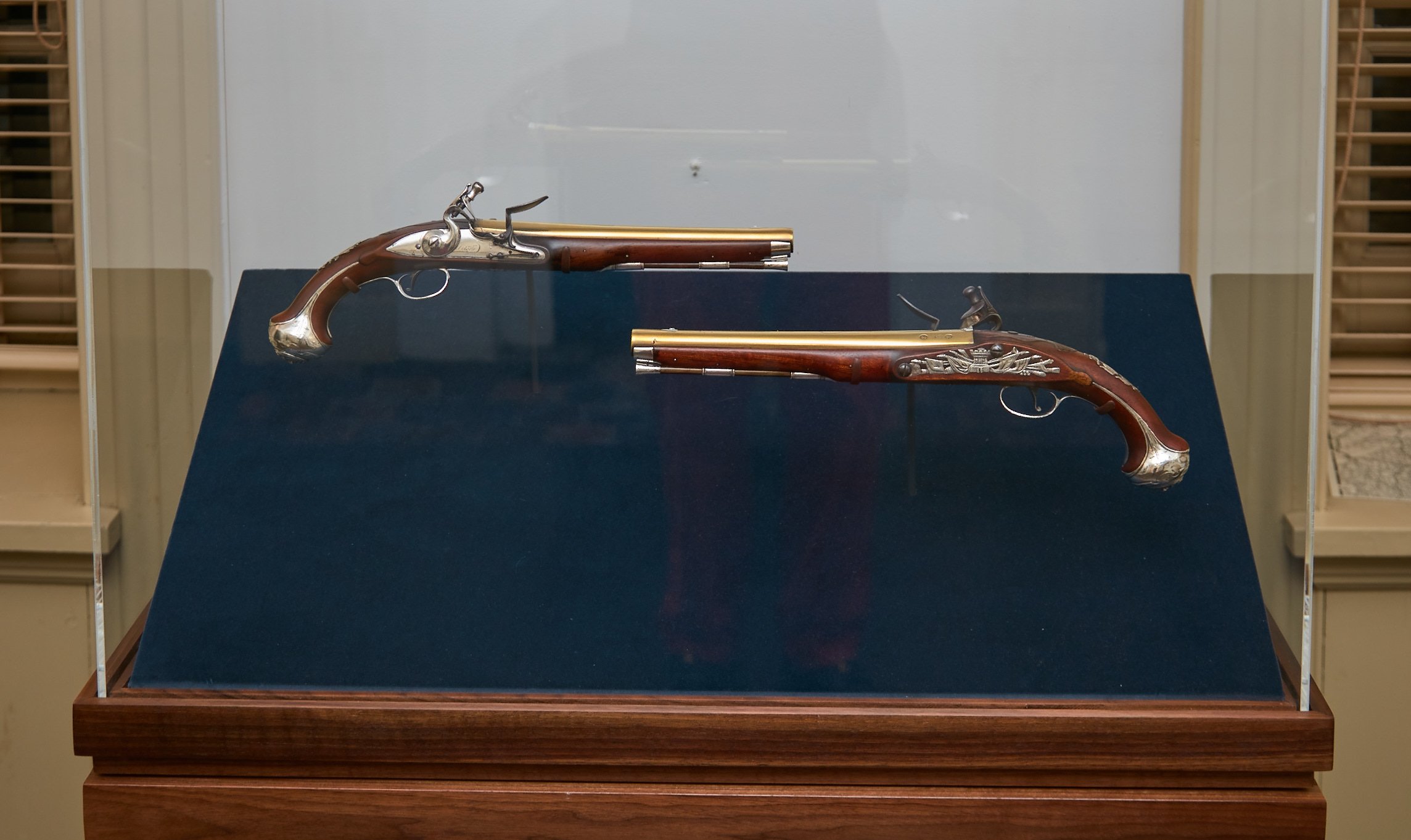

As Anthony grew older, he took up horse racing and pistol shooting. He seemed clearly to be readying himself to become a soldier himself.

Two of great war heros and strategists that Wayne read about and idolized during his boyhood years included Julius Caesar and Maurice de Sax, a German and French general. When he later served as a adult in the American Revolution, Wayne would often utilize their tactics in battles and cite their words in his communications

-

When Anthony was of school age, he was sent to Philadelphia to be educated at his Uncle Gabriel Wayne’s academy. Wayne later studied at the College of Philadelphia, though he didn’t graduate.

But education was never Wayne’s primary passion, which exasperated his uncle. Feeling that his nephew first needed to apply himself to his education, Gabriel wrote to Anthony’s father Isaac, sounding the alarm. But he too had also witnessed Anthony’s passion for the military:

''I really suspect that parental affection blinds you, and that you have mistaken your son's capacity. What he may be best qualified for, I know not - one thing I am certain of, he will never make a scholar, he may perhaps make a soldier, he has already distracted the brains of two-thirds of the boys under my charge by rehearsals to battles, sieges . . ."

Isaac proceeded to have a long talk with his son and Anthony finally started applying himself to his schoolwork, mathematics in particular.

Throughout his upbringing, Wayne would clash with his father on the topic of his future profession. He of course wanted his son to follow in his footsteps and become a gentleman farmer.

Eventually Wayne's love of the outdoors and knack for mathematics led to his interest in pursing land surveying. In 1765, he was sent by Benjamin Franklin who owned land in Nova Scotia to survey property there.

While in Canada, Wayne also assisted in starting a settlement at Monckton, New Brunswick which Franklin’s firm, the Philadelphia Land Co., controlled.

-

After a year in Canada, Anthony returned to Waynesborough to help his father develop the family farm and the tannery.

In 1766, Wayne married Mary “Polly” Penrose and they had two children: a daughter Margretta born in 1770, and a son Isaac born in 1772.

Eight years later, in 1774, Wayne inherited Waynesborough and all of its property.

Because of his father’s prominence, Anthony decided like many of his wealthy peers to enterer into politics. He would serve in the Pennsylvania Assembly and on his local Committee of Public Safety.

As tensions with Britain mounted in the Colonies, Wayne encouraged his community to support rebellion against the British government.

With the outbreak of the war in 1775, Wayne joined the Continental Army and raised a regiment.

By January of 1776 he had been commissioned as a Colonel in the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Army. He would finally have his chance to be a soldier.

-

Wayne’s first mission of the war was to reinforce the Continental Army’s Canadian expedition in June of 1776. His first combat service began with the American defeat at the Battle of Three Rivers, where Wayne was wounded.

Wayne spent the following winter in command of Fort Ticonderoga and in February 1777, he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General.

Brave, fearless in action, and dogged in his pursuit of the enemy even when wounded, Wayne charged his way through the battles he fought with commitment, vigor and a relentless work ethic.

His most brilliant campaign was at Stony Point, NY, in June of 1779, where Wayne stormed the British fort and recorded one of the more notable victories of the war, providing a critical boost in morale to the American troops.

The other key war battles where Wayne participated included all the major battles of the Philadelphia Campaign 1776-1777: Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, Valley Forge, and Paoli.

Wayne was also present with the Continental Army when the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781. Having become one of General Washington's most respected and trusted officers, Wayne was promoted to Major General in 1784.

-

General Wayne had his greatest success in the period following the American Revolution.

In 1792, after two American commanders had suffered crushing defeats in their attempts to secure the Northwest Territory for America, President Washington had to take decisive measures.

He called upon the now retired Anthony Wayne and commissioned him to be the new Commander in Chief of the Legions of the United States, an army of even greater size than had previously been put forth.

General Wayne was to travel to the Territory (the Midwest today) with the assignment of raising and training this new larger army to defeat the united Indian nations allied with the British.

Wayne’s Success Was Multifold With Lasting Implications. Wayne was more than successful in achieving American victory here. His decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, and the subsequent Treaty of Greenville secured the Territory once and for all for our new nation.

This success opened the way to westward expansion and ending for all time British power on American soil.

A third American defeat might have led to ceding the area to Great Britain or even invasion by Spain or France who also coveted the territory. And it also would have threatened the power of our new government. So Wayne's victory in the Northwest campaign had extraordinary implications.

A Hero’s Welcome. General Wayne returned home to a hero's welcome. He was ushered into Philadelphia by three Troops of Horses with a salute of cannons, ringing bells and thousands of people cheering his victory.

Banquets were held in honor of General Wayne and his troops at City Tavern and later at Richard’s and Weed’s Taverns.

Wayne’s Death. In June 1796, during a trip back to the frontier to oversee the surrender of British forts, Wayne became ill with gout. On Dec. 16, 1796, Anthony Wayne died at Fort Presque Isle and was buried in present-day Erie, PA.

In 1809, Anthony’s son Colonel Isaac Wayne, traveled to Erie to remove his father’s remains and bring them home to be reinterred at the family plot at St. David's Church in Radnor, Pennsylvania.

Honored Far and Wide. General Anthony Wayne has been much honored since his death. Major U.S. towns, cities and counties are named for Anthony Wayne.

In total, 16 counties, 7 cities, 10 towns, 8 townships, 5 forests and parks, and numerous schools and colleges, streets and highways, and monuments and sculptures, including Fort Wayne, IN, Wayne County, MI, Waynesborough in Burke County, GA and Wayne State University (and many others) are named in General Wayne’s honor.

Anthony Wayne’s legacy also includes the naming the superhero character of Batman, Bruce Wayne.

Wayne, the Revolution & Securing the ‘West’

-

Quebec Canada Campaign. In the Spring of 1776, Wayne and his regiment were sent to reinforce the remnants of Benedict Arnold’s Canadian expedition, which was retreating south after a disastrous campaign against Quebec.

Wayne was recognized both for fighting a successful rear-guard action at the Battle of Trois-Rivieres as the Americans retreated to New York and for fortifying U.S. positions in the event the British opted to pursue.

For his service, Wayne was promoted to Brigadier General in February of 1777 and spent the winter in command of Fort Ticonderoga, N.Y.

Battle of Brandywine. In the spring of 1777, Wayne and his PA command returned south to join General Washington’s forces as they sought to protect Pennsylvania from General Howe’s British troops.

American intelligence failures combined with successful British maneuvers, which split the American forces, led to significant defeat for the Americans at Brandywine on September 11, 1777.

But Wayne’s smart defensive tactics enabled his troops to hold off Hessian forces twice their number for three long hours until Wayne was ordered to retreat, which protected the American right flank and kept the defeat from being even worse.

After the battle, which was the largest land battle of the Revolution, General Washington praised Wayne in a letter he wrote from Chester to the President of Congress:

“Wayne improved upon the plan recommended by me, and executed it in a manner that does signal honour to his judgment and his bravery…The troops withdrew, but there was no panic, and they are in fine spirits, ready to meet the enemy...”

Battle of Paoli. In order to slow General William Howe's advance towards Philadelphia, Wayne was ordered by Washington to harass the enemy’s rear.

But in a surprise night attack on Wayne’s sleeping rear-guard at Paoli Tavern, on September 20th, 1777 British General Charles Grey ambushed Wayne’s troops. They suffered dozens of casualties and Wayne barely escaped capture.

General Grey had ordered his men to remove their flints and attack with bayonets and swords in order to keep their assault secret, earning Grey the nickname of ‘General Flint’. The high number of casualties led many to label the attack a massacre, but many historians now argue that the Americans exaggerated the incident for propaganda purposes.

In order to clear his tarnished reputation, Wayne requested his own court martial and he was cleared of any wrongdoing unanimously by a military court, “Wayne did every duty that could be expected from an active, brave and vigilant officer, under the orders which he then had. The Court do acquit him with the highest honor.”

Battle of Germantown. The Continental Army now set their aim on recapturing Philadelphia. Washington saw an opportunity to entrap the British army which Howe had divided. Howe had moved 9,000 of his troops to Germantown, but left more than 3,000 in Philadelphia.

Washington’s audacious, ambitious battle plan called for four columns of troops to attack from multiple directions, with General Sullivan’s and Wayne’s commands charged with leading the offensive against the British center lines. Washington’s hope was that the British troops would be surprised like the Hessian troops had been at the Battle of Trenton.

By early morning of October 4th, 1777, the Americans had the British retreating, but Washington's plan was soon thwarted when one of his four columns lost its bearings in a dense fog that had set in.

Others columns failed to coordinate effectively. General Sullivan’s line which had initially routed the British, took heavy fire. As they withdrew, they exposed Wayne’s Pennsylvania Line which collided with General Green’s late arriving forces in the increasingly impenetrable fog made worse by smoke from firearms coming from Cliveden House where the British had barricaded themselves.

Mistaking each other for the enemy, the American’s began firing into their own lines. They were forced to retreat in some disorder.

While the Battle of Germantown was a defeat for the Americans, the Continental Army had finally gone on the offensive and attacked the British, giving our troops a new confidence. Howe had once again failed to finish the job, enabling Washington to escape with his army in tact.

But more importantly, the French Court was also observing this battle. They saw Washington and his troops showing audacity and passion, proving that America might in fact be a worthy ally. Historians believe the French were as much influenced by the Battle of Germantown, as they were by the defeat of the British and the surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga.

-

Valley Forge and Battle of Monmouth, NJ. Washington's army along with General Wayne and his Pennsylvania Line spent the long winter of 1777 at the Valley Forge encampment where they suffered from relentlessly harsh winter conditions and alarmingly insufficient supplies of food and clothing.

Despite these obstacles, Washington used the opportunity to train his men into a unified fighting force with the help of former Prussian military officer Baron Von Steuben.

On June 18, 1777, the day after the British evacuated Philadelphia, Washington’s Continental Army marched out of Valley Forge and made their way towards the coast of New Jersey, with renewed confidence.

By the 24th, with the two armies within a few miles of each other, Wayne wrote General Washington urging an immediate attack. Despite significant opposition from his other generals, Washington followed Wayne's advice and ordered the attack.

Wayne’s command, serving under Major General Charles Lee, made first contact with the enemy. The cautious Lee however disobeyed Washington’s order and retreated.

Without Lee’s reinforcements, Wayne's forces were pinned down by the larger number of British troops. Nevertheless Wayne and his men held out, fighting intensely and holding the center until relieved by troops sent by Washington.

The British advanced, but they’d been checked by Wayne and his troops. Eventually they’d had to retire in disorder, but during the night, the Americans made their way to New York.

General Washington singled out Wayne in his report to Congress:

“I cannot forbear mentioning Brigadier-General Wayne, whose good conduct and bravery through the whole action deserves particular commendation.”

Battle of Stony Point, NY. In July of 1770 at Stony Point, Wayne recorded one of his most notable victories of the War. The fort was one of the key strategic British defenses along the Hudson River, under the command of Lt. Colonel Henry Johnston. 150 feet high, at the top of the rocky palisades, the fort was protected by a force of some 600 British troops and significant artillery both in the fort and across the Hudson.

Wayne had contemplated the capture of Stony Point for some time, and he had finally convinced Washington it could be done. Wayne reportedly said to General Washington, “Issue the order and I’ll storm Hell!”

At Washington’s request, Wayne assembled a small, elite corps of soldiers from 5 states (the equivalent of today’s Special Forces) to proceed in a daring and highly secretive mission.

Wayne used all he had learned from his defeat at Paoli. He led his troops in a meticulously planned, surprise nighttime attack, which began with a silent, bayonets-only assault.

Wayne received a severe scalp wound from a musket ball, which stunned him initially, but he continued on. Despite heavy resistance and the fort’s many physical obstacles, Wayne’s assault was successful and in just a few hours he had captured the Stony Point fort and its 543 British prisoners.

In his message to Washington reporting the victory, Wayne wrote: “The fort and garrison with Col. Johnston are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free.”

The storming of Stony Point and victory was a significant morale booster for the Americans and was widely recognized as one of the most brilliant maneuvers of the Revolutionary War.

On July 16, General Washington congratulated Wayne and his troops on their outstanding victory. Congress unanimously passed resolutions praising Wayne and his men and awarding Wayne a gold medal commemorative of his gallant service.

-

Savannah and Charleston. After Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, Wayne was sent to join General Nathanial Green’s army in the South to drive the British out. Savannah, GA and Charleston, SC were still occupied by the enemy and physical possession would be key in any peace negotiations.

Wayne served largely in Georgia. And despite the fact that he had too few men, weapons or food, he defeated the Creek Indians who were allied with the British in June of 1782 and secured Savannah after the British had evacuated.

On learning of General Wayne’s success, General Greene wrote to Wayne on July 14th:

"I am very happy to hear that the enemy have left Savannah, and congratulate you most heartily on the event. I have forwarded an account thereof to Congress and the Commander-in-Chief expressive of your singular merit & exertions during your command and doubt not that it will merit their entire approbation as it does mine."

In December of that year, Wayne and his men were the first Americans to enter Charleston, SC, following the British evacuation.

GA’s Gift to Wayne. After the war, Georgia was so appreciative of Wayne’s service that the state purchased two rice plantations (first ‘Richmond’, then ‘Kew’) for Wayne totaling 1,300 acres near Savannah in gratitude for his “great merits and services.” Wayne subsequently became a planter, but his attempts at farming in GA, left him mired in debt.

Rice is a difficult crop to farm, especially on land that had been neglected and was in need of costly repairs. Not to mention the fact that farming was never Wayne’s strong suit. Rice is also a labor intensive crop, which prompted Wayne to purchase enslaved workers and equipment, which he financed (after a loan fell through) by mortgaging his farm in PA, Waynesborough.

Running for Congress in GA. After five years and high hopes, Wayne’s rice plantation operations were not going well financially. Hoping to forestall his PA creditors who had backed his loan against his Waynesborough property, Wayne decided to run for Congress in GA.

Wayne was elected to the Senate, but after two years, he had to resign his seat because of controversy over whether his residency was in fact in PA and not in GA.

But by then, Wayne’s creditors had agreed to settle his debts by confiscating his GA properties—including his enslaved workers—as payment for his debts which included the mortgage he had taken out on Waynesborough.

Wayne returned to his farm in Waynesborough chagrined and aggrieved, but also relieved to be returning home.

-

Two Crushing Defeats. Washington Calls Upon Wayne. In an effort to stake a conclusive claim to territory ceded by the British under the terms of the Peace of Paris (1783) Treaty and to protect the safety of American settlers, the American government had sent forth a series of expeditions to the Northwest Territory.

The first expedition, under General Josiah Harmar, was ambushed and crushed in October 1790. The second, led by Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair, Wayne’s old nemesis, was routed on November 4, 1791, in one of worst defeats ever suffered by the U.S. military against a Native American force. More than 700 Americans died, including 56 women who had accompanied their soldier husbands.

The Native American force — a Confederation of seven mostly Algonquian-speaking Tribes — were heartened by these victories and their belief that they owned the land by moral right and prior treaty. They were further buoyed by their explicit promise of support from the British.

The Confederation had proven to be a strong ally and trading partner. The Territory was a lucrative source of furs for the British and in exchange, they supplied the Native Americans with bullets, powder and guns, along with the promise of protection.

President Washington Takes Charge. Having been humiliated twice by these defeats and seeking to put an end to the violence with the British-backed Indians, President Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of defeating the Confederacy.

And who did Washington call up from retirement to command this newly formed ‘Legion of the U.S.’? None other than the formidable tough-as-nails Anthony Wayne.

In March 1792, Congress passed a bill increasing the size of the army to more than 5,000 men with Major General Wayne as its new Commander.

Relentless Training. Wayne took command in July of 1792. He traveled to Western PA near Pittsburgh and began immediately training his men. Unlike the two previous expeditions which had relied on inexperienced troops, Wayne created the first facility in our nation to train recruits and turn them into professional soldiers.

While negotiations dragged on between the tribes and Washington’s administration, Wayne spent more than two years training his men, first at Fort Fayette, PA, and then at Legionville, PA, awaiting orders to begin his invasion.

Wayne knew the cost of sending untrained men into battle from his own experiences and his knowledge of military history. So he was merciless and exhaustive in his efforts, instructing his men in close-order drills, bayonet combat and personal marksmanship. By the time he was ready to mobilize his troops in the fall of 1793, Wayne’s legion had developed into a disciplined, skilled military force.

Diplomacy Fails. On September 11, 1793, Washington send word to Wayne that negotiations had failed. Wayne then advanced with his 2,600 troops to Fort Jefferson, OH.

On October 17, a contingent from one of the tribes attacked a nearby supply convoy requiring Wayne to add more troops to guard his supply line. With these new security issues, Wayne opted halted major operations and built Fort Greenville, north of Fort Jefferson, where his troops would spend the winter.

Fort Recovery, OH. On December 23, 1793, Wayne led a small group of men north to the site of St. Clair's defeat. Here he gathered up the American dead still on the battlefield and built Fort Recovery. Indian scouts, spying on Wayne, started calling him "the Chief who never sleeps."

In June of 1794, 2,000 Indians attacked the fort. And although the Indians greatly outnumbered Wayne’s forces, Wayne’s skilled and well-trained force was able to hold out against overwhelming odds.

The Indians were forced to retreat which shook their confidence and further divided their leadership, with some tribes breaking off from the Confederation.

Wayne continued moving north, next establishing Fort Defiance, OH in August 1794. Ahead of him were some 1,300 Indians camped outside of the British-held stronghold, Fort Miami (southwest of today’s Toledo, OH). Wayne sent one more letter to the tribes with a final offer to negotiate. He received no reply.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers. On August 20th, Wayne’s trained and seasoned regulars, together with some 1,000 mounted Kentucky militia, met 2,000 of the Confederation’s warriors near Fort Miami for a final confrontation.

In a ravaged section of forest in present day Maumee, OH, Wayne’s Legion routed the warriors and effectively ended Indian resistance in a battle lasting less than an hour.

Fleeing Indians had raced toward Fort Miami, where the British had promised protection. But they were turned away. The British had become enmeshed in the Revolutionary Wars in France and did not want to risk a new confrontation with the U.S.

This victory enabled Wayne to negotiate the highly favorable Treaty of Greenville in August 1795. The defeated tribes had to cede extensive territory, to the U.S. including most of Ohio and large sections of IN, IL and MI. The Indians had been left with no other option, as the previously signed Jay Treaty (November 19, 1794) had required the British to agree to evacuate all of their outposts in the Northwest Territory, so the Indians knew they’d be left with no ally.

-

Personality Traits. That Controversial Nickname. Descriptions of Wayne cover the gamut from determined, disciplined, bold, strong tempered, a lifelong student of military history, politically astute, a great writer, highly analytical, a night owl, and detail oriented to impetuous, rash, colorful, a stickler for rules, a harsh disciplinarian, stubborn, obsessive, a risk taker, vain, aggressive, along with dapper, a meticulous dresser, and a womanizer.

Most experts believe he was all of these, but that the nickname that is most quoted ‘Mad Anthony’ is misunderstood. While Wayne was indeed daring and aggressive in his leadership style, he was also noted for his meticulous planning, encyclopedic knowledge of military history and tactics, his relentless attention to training and his loyalty to his troops and to General Washington.

General Wayne’s grit, skills, tactical boldness, personal courage, his successes even in battles lost together with his nine years of service to our country and the fact that he was five times wounded in battle and died while in service make clear that the connotations of the moniker of ‘Mad Anthony” does him a disservice.

Yes, he had a formidable temper like many leaders and he was a champion cursor, but he was not reckless or mad.

Origins of the Nickname. ‘Mad Anthony’ likely came about during the winter of 1781 when a disobedient soldier who Wayne used occasionally as a spy became disobedient and drunk and was ordered to the guardhouse. The soldier, a chronic deserter known as ‘Jemmy the Dover’, demanded to be released and asked that a messenger be sent to General Wayne to intervene.

Wayne angrily refused and instead ordered the culprit to receive 29 lashes across the back for his disorderly conduct and desertion.

Jemmy reportedly responded, "Anthony is mad. He must be mad or he would help me. Mad Anthony, that's what he is. Mad Anthony Wayne!"

This story quickly spread throughout the Continental Army. ‘Mad Anthony Wayne’ had a cadence to it that caught on with the soldiers. Newspapers later used it too.

‘Dandy Wayne’ was another often used nickname, even before ‘Mad Anthony’ came about. General Wayne was a meticulous dresser with a preference for ruffled shirts under an immaculate blue uniform coat with white facings. Wayne liked looking dapper in part to dazzle the ladies, a weakness in character which over the years damaged his relationship with his loyal wife Polly.

Loyalty to his Troops and their Needs. One of Anthony Wayne’s great traits was his loyalty to his Pennsylvania troops and to General Washington.

Wayne would do anything the General asked of him. During the frigid winter at Valley Forge, Washington tasked Wayne and another young general, Nathanial Green, with what was perceived as a degrading chore: scouring the countryside for cattle, sheep, and hogs from farmers to feed the starving Continental Army.

Despite the mocking and name calling by nearby British troops for having to take on such lowly tasks, Wayne didn’t complain. The troops needed food.

The troops also lacked adequate clothing, a huge problem particularly during Winter. An issue General Wayne had been addressing as early as that spring when he began writing letters urging his superiors to send supplies for his troops.

Later that year, in a letter to Washington during their Valley Forge stay, Wayne writes of the “Distressed and Naked Situation of our Troops.”

At least a third of the troops had no shoes or blankets. Many did not have a proper coat to protect against the icy rain that winter.

Washington of course was equally alarmed by the situation. While both General Layfayette and the Oneida Tribe did bring in some supplies and food, it wasn’t enough. So Washington had to plead relentlessly to Congress for provisions.

In one letter to the President of Congress, Washington wrote in stark terms about the dire situation, “We had in camp…not less than 2,898 Men unfit for duty by reason of their being bare foot and otherwise naked.”

Wayne Assists in Writing to Congress. Knowing how well Wayne wrote and argued, Washington also tasked Wayne with lobbying Congress. Wayne was all too happy to oblige, sending off scathing letters to the politicians, demanding supplies and even questioning their manhood. In one letter, Wayne wrote of “the worn out coats and battered linen overalls”…and blankets which had to be “divided among three soldiers. ”

His letter went on to state that, “Our soldiers…have now served our country with fidelity for nearly five years, poorly clothed, badly fed and worse paid…they have not seen a paper dollar…for near twelve months.”

The following January, 1778, Wayne wrote still more letters. He had even bought cloth at his own expense, but the government had failed to turn the cloth into new uniforms.

Wayne’s troops loved him for this passion and his commitment to their needs. It took until later that winter before Wayne’s requests for significant supplies of clothing for his PA men were met.

But it was not through the politicians, but as a result of the efforts of Esther Reed and Sarah Franklin Bache who had organized a committee of Philadelphia women to go door-to-door for contributions to help clothe their beloved PA troops.